CICADA

The Forest, 2017, oil on canvas, 90 x 60cm

Seventeen years, no sick day, no mistake, 2017, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

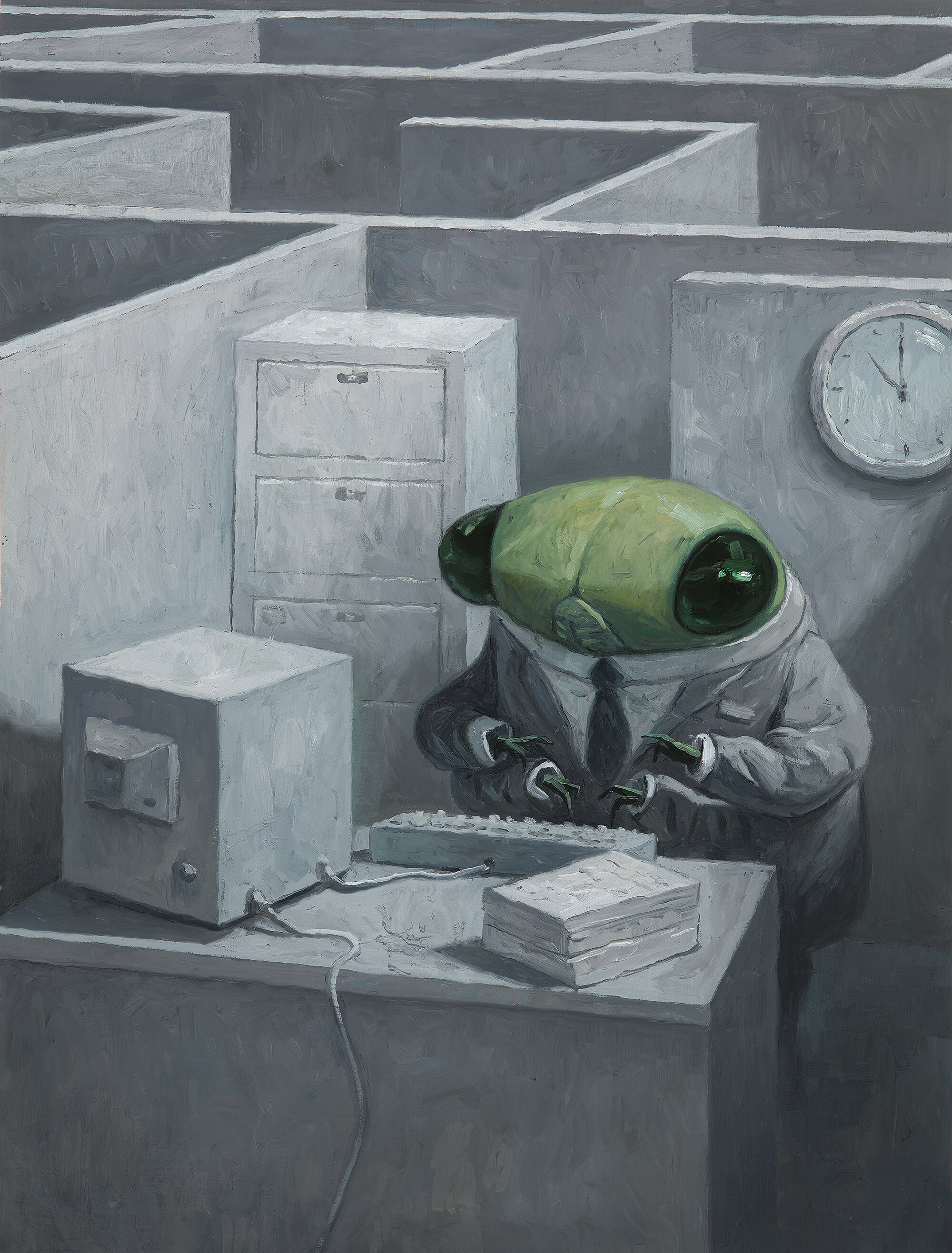

Desk Job, 2017, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

Human resources, 2017, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

Co-worker no like Cicada, 2017, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

Cicada (cover), 2017, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

Cicada is the story of an insect working in an office, and all the people who don't love him. It's a very simple 32-page picture book about the unspoken horrors of corporate white-collar enslavement... or is it? You never can tell what a bug is thinking.

The earliest idea for Cicada came during a visit to Berlin around 2005, although it could have been any city at any time: I was looking at the imposing grey façade of an office building, studded with hundreds of grey windows. In one window, and one window only, someone had placed a bright red flowering plant to catch the sun. I remember joking to a friend that maybe a big insect, a bee or something, worked in that cubicle. It was a thought I recalled subsequently whenever I saw something organically out-of-place in the sterile environment of corporate office spaces. A particularly lonesome pot plant, an employer’s cat or dog brought in to work, a lost sparrow or, of course, a bug pitifully trying to escape through a glass window.

A second source of inspiration came from hearing cicadas outside my bedroom window, and sometimes finding their empty casings – the cast-off skin of the nymph – still clinging to a high wooden fence (there are large lime-green cicadas in Melbourne that I’d rarely seen in Perth, where I previously lived). Elsewhere I’d seen a documentary about the life cycle of cicadas, in which they spend up to 17 years underground before emerging all at once, overwhelming their predators, then mating and dying in a brief glorious period. It seemed like a kind of heightened awareness of life compressed into a very short final act. This long cycle is alien to us humans, but it’s interesting that we still find it fascinating, as if buried there is some metaphor about mortality, endurance and perhaps even love.

I wanted to create a picture book that, as usual, was not particularly for children (while still accessible to them). I was thinking about friends and family who have worked in places where they felt underappreciated, including my father who had mixed experiences in his professional life, and has since happily disappeared somewhere in his garden since retirement, growing everything from olives to custard apples.

Publication date: June 26, 2018 (Australia) Also published: US, UK, France, Spain, Sweden, Denmark, China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Poland, Turkey, Czech Republic, Italy, Germany, Norway.

*

Stories abound of the disillusionment of workers within large corporations and businesses. A friend of mine with an extensive career in one of the bigger tech firms retired feeling quite bitter at the wasted decades of devoted service in a company that, in the end, did not value him highly. I was also influenced by dreadful reports of a tech factory in China that installed ‘suicide nets’ around their buildings to prevent workers from jumping to their deaths. Corporations sometimes sustain the an illusion of having primarily human interests – the welfare of workers and customers – when those interests are frequently secondary to far more abstract financial ones. The 2003 Canadian documentary The Corporation presents the interesting and compelling view of corporate entities as psychopaths in this regard, a problem of how they are legally defined and politically empowered, quite improperly, as we see when such institutions crash or impartial investigations are allowed (such as a royal commission into entrenched banking malpractice in Australia around the time of Cicada’s publication). I’ve always been interested in the ways that social, political and economic structures, originally created to promote human interests and with genuinely good intentions, can actually end up being very dehumanizing and counterproductive. We are easily enslaved by the very systems that are meant to work for us, and maybe even morally influenced by their bad logic, easing the way for ethical compromises by confusing our judgement of value. From fake spreadsheet forecasts to workplace bullying, institutional structures often facilitate a slippery scale of moral apathy and transgression, things to which we all have inclinations as humans.

Works of art and literature are also necessary influences for any story, no matter how small. Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915) of course comes to mind. While I only noticed the parallels of Cicada with Gregor Samsa, the salesman who wakes up one day as a giant bug, quite late in developing my story, it’s always been one of my favourite surrealist tales. George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) continues to be an influence, as well as 1984 (1949); Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil (1985), not unlike a comedic version of 1984 also continues to inspire Cicada as it did my picture book and short film The Lost Thing. There are several Gary Larson cartoons about big bugs that have always amused me, and one in particular about a high-flying executive insect who is now homeless because a co-worker one day pointed out ‘Hey, he’s just a big cockroach!’ I would also have to cite both the British and US versions of the mockumentary sitcom The Office (2001-2013) as influences; Mike Judge comedy Office Space (1999), and Jacques Tati’s visual critique of 1960s living and work spaces in Playtime (1967), a period when these kind of human aquariums must have been relatively new. Interestingly, I’ve never in my life worked in an office cubicle of for a large company, and perhaps this is one reason I find these environments fascinating, both visually and narratively. They are like the science fiction sets of a movie made a long time ago: an imagined future that might be either utopian or dystopian – it’s hard to tell! I find them both attractive and unsettling, and that’s the kind of ambivalent feeling that typically inspires me to write and draw stories.

The visual development of Cicada is also influenced by my experience with theatre and film production, of how you can tell a story with minimal props and sets. For Cicada, I began by sketching out thumbnails of different possible incidents involving an insect working uncomfortably alongside humans. Instead of developing these as more detailed drawings, as I usually do, I made a sculpture of the central Cicada character with moveable limbs -– basically an action figure – and built simple miniature office spaces out of paper and board. I could then arrange and light these elements on a table-top, photograph them, and use the resulting images as ‘sketches’ for both structuring the story and as reference for final paintings. In some cases, the finished illustrations are nearly identical to the photographs, and shows how useful this process can be in exploring scene variations, not unlike stop-motion film-making.

I thought about having the entire book as photographed puppets and sets, but there is something about the transition to oil-painting, particularly with loose strokes, that gives each scene an otherworldly quality, and the scale of the world seems larger in the imagination. It also makes it easier to blend together those scenes that are very difficult to fabricate physically – the forest, long stairwells and so on. The human figures are based on photos of myself posing in a suit, both bossing and bullying the cicada, which could be then be grafted into paintings by matching the lighting effects in a painterly way.

What is the resulting story about? Well as usual that is a question for the reader. My own interpretation has changed during the long period I’ve been thinking about Cicada, and then creating final illustrations and text, which tend to exert their own imaginative pressure. That is, I listen to what the story seems to be telling me to do, work on getting it right, and then speculate more deeply about meaning later (like now). I also try to keep it very simple. I used to think this story was mostly about workplace bullying, and this was the emphasis in early notes, research and extensive storyboards. But the part I mostly think about now is the fact that the Cicada is amused by humans the whole time, but we only know that his signature refrain ‘Tok! Tok! Tok!’ is the sound of something unexpected. Maybe the story is less about corporate slavery than the power of personal attitude or direction. That is, the same situation – especially one in which you are trapped – can be depressing or amusing depending upon how you look at it, react to it, or think beyond it. The cicada has a very different perspective on time, purpose and liberty, and this is one possible interpretation of the Basho haiku I decided to include at the end of the book.

Calm and serene / The sound of the cicada / Penetrates the rock

Of course, we never know how the cicada is really feeling. We assume this underappreciated employee must be miserable, but we may be mistaken. The other side to this thought is to wonder about the sterile environment of the story, or any institution populated by uncaring, aggressive and basically unhappy humans, and think about the ultimate purpose of it. Who is really suffering these absurd conditions? Not the cicada.