MEMORIAL

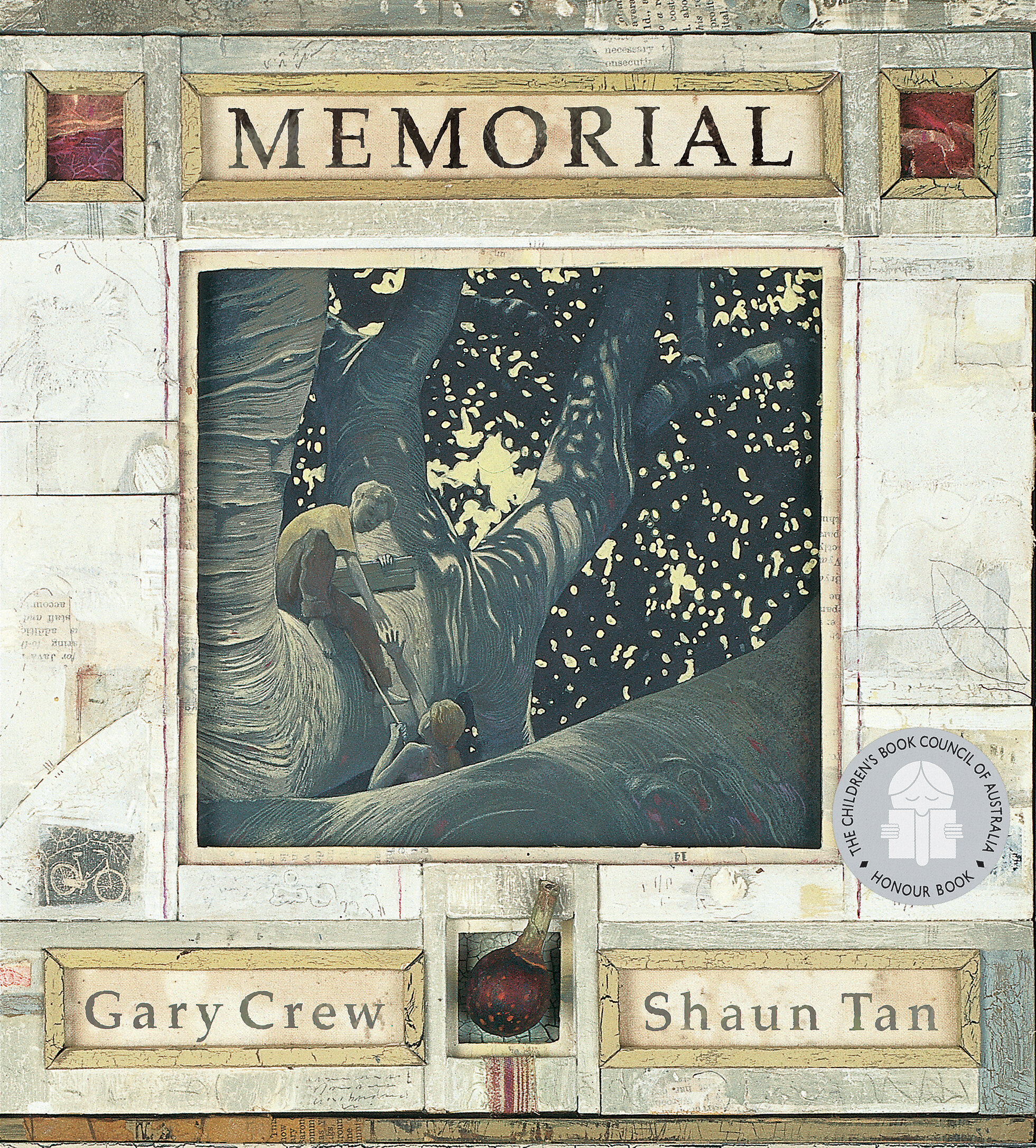

Summer tree, 1998, acrylic, gouache, pencil, collage on paper

Great Grandpa, 1998, acrylic, gouache, pencil, collage on paper

Roots, 1998, acrylic and oil on canvas

Unreturned (detail), pencil on paper

Memorial (1999) is a story about a tree planted beside a war memorial monument in a small country town by returned servicemen. Years on, the tree has grown to be huge and unruly, dislodging the statue next to it and creating a traffic hazard in what is now a much larger, busier town. A decision is made by a local council to cut the tree down, prompting four generations of one Australian family reflect on the true nature of memory, both private and public.

*

Author Gary Crew and I collaborated quite closely in developing both text and illustrations, such that the two married in a way that was understated and thought provoking. What made the book especially engaging for both of us was that it ended up being not about war, memorials or remembrance as ‘grand’ subjects, but rather the small, quiet memories that make up ordinary day-to-day lives. Really about the complex nature of memory itself. I tried to capture this in illustrations which were fragmented, sometimes worn and faded, relating to Gary’s anecdotal style. I incorporated collage into paintings and drawings to this effect, using fabric, leaves, wood, rusted metal, photographs, newspaper, dead insects and other found objects. Because of this assemblage, many of the images were not flat or could be scanned in the normal way, and had to be photographed instead.

The story is made up of different family members reminiscing about things that happened to them near this particular tree, but I didn’t want to show the narrators in any literal way, or even what they were talking about directly (and with Gary’s writing, this was not necessary anyway). As a result, most of the illustrations are about building up mood in a metaphorical way - a broken kite, some coloured teacups, a germinating seed, a beetle taking off and landing, and so on. We don’t see a lot of things, including the tree being cut down, but we get a sense of it instead, as if everything is silent memory recollected.

Given precedents of other picture books about war (such as Michael Foreman’s excellent War Game), it was a case of trying to do something different. Most young people growing up in suburbia, like myself in 1980s, have little experience of war, and words and paintings can only really reclaim feeling from an audience, they can’t invent it. Even though everyone’s lives have been affected one way or another by the past century of conflict, probably the worst in human history (knock on wood), the memory of it and ensuing sentiment is not simply inherited.

There is also a possibility that such cultural memory is lost in the abstractions of nationalism and ceremony, if the symbol does not bear direct witness to it’s own content. A minute’s silence is not in itself pregnant with meaning. The concrete monument in Memorial, similarly, does not speak for itself - neither does the ‘other’ monument of the growing tree; they have to be invested with thought and feeling from the ordinary people underneath. Perhaps the point of this picture book is to open a passage for its readers to think about the way symbols really work in relation to collective memory, as a container that needs to be continually topped up to have any currency.

As an illustrator, there were three key concepts that informed the painting and design of the book. The first was the use of various materials in fragmentary pieces to emulate the ‘texture’ of memory. We don’t remember things as we actually experience them, with the continuous clarity of videotape, but instead see the past in our mind as fading snippets and vignettes, vulnerable to the distortion and decay of dreams. Odd small things can trigger memory in quite a personal way - odour being the most obvious one - but also visual details that at a glance may seem banal; the colour of some fabric, a pattern of cracked tiles, a pressed flower, a cracked wooden joint or a teacup. The fact that the page layouts are not continuous, shifting from one environment and mood to the next, and involve attention to such objects, was an attempt to make the book feel like a memory, rather than an experience.

The second key idea, and one that underscores my general approach to illustration as mentioned elsewhere, was that the pictures would not clearly ‘illustrate’ the text. I spoke to Gary about this from the outset in terms of ‘tangents’, that the pictures would wander off-course from their primary subject (a discussion of a war memorial), as conversation often does. So there would be some glimpses of experience outside of the text, which aren’t necessarily clear. Also, I was keen to refrain from illustrating any of the speakers; the exception being the great grandfather who introduces the story, literally fading into the kind of patterns that make up the rest of the pictures, and the boy at the end who we only glimpse from behind. Mostly, there are just indirect traces of what is spoken of, where the presence of the narrator is implied rather than ‘illustrated’.

Similarly, the timing of the visual and written narrative are actually discordant, especially towards the end where three generations are discussing the possibility that the local council may soon cut down the tree, and I have illustrated the tree having already been cut down. This might further suggest that all the conversations in the text are themselves the memory of the young boy, who may now be an adult.

The third concept was to remove the text altogether from certain pages and look at the ability for an illustration to tell a ‘story’ without narrative, and also to stop the reader from reading in order to look. Although I love the medium of picture books, in many ways I find words and images to distract from each other - they can be a liability as much as a convenience when it comes to creating meaning. I was particularly interested in the idea of silence to add further depth to the book, that there are great reserves of feeling which cannot be expressed in words, and that the stories only ‘skim’ over the top of these lakes. Gary’s text offered several opportunities for visual ‘intermissions’ where characters avoid talking about something that causes pain for them, or simply run out of things to say.