TALES FROM OUTER SUBURBIA

The Amnesia Machine, 2007, pencil 40 x 40cm

The Family, 2007, acrylic and oil on paper, 70 x 50cm

The Visitor, 2007, acrylic and oil on paper, 70 x 50cm

Sunday Afternoon, 2006, oil and acrylic on paper 70 x 50cm

The Water Buffalo, 2006, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

The Nameless Holiday, 2006, scraperboard, 45 x 30cm

Our Tuesday Afternoon Reading Group, 2004, acrylic and oil on paper, 50 x 40cm

Tales from Outer Suburbia is an anthology of fifteen short illustrated stories based on my memories of growing up in the northern suburbs of Perth, Western Australia. Each one is about a strange situation or event that occurs in an otherwise familiar suburban world; a visit from a nut-sized foreign exchange student, a sea creature on someone’s front lawn, a new room discovered in a family home, a sinister machine installed in a park, a wise buffalo that lives in a vacant lot. The real subject of each story is how ordinary people react to these incidents, and how their significance is discovered, ignored or simply misunderstood.

*

‘Outer Suburbia’ might refer both to a state of mind as well as a place: somewhere close and familiar but also on the edge of consciousness (and not unlike ‘outer space’). Suburbia is too often represented as a banal, quotidian, even boring place that escapes much notice. Yet I think it is also a fine substitute for the medieval forests of fairytale lore, a place of subconscious imaginings. I’ve always found the idea of suburban ‘fantasy’ very appealing, in my own work as well as those of other writers and artists, because of the contrast between the mundane and extraordinary, the effect of which can be amusing or unsettling, and potentially thought-provoking.

I had also been thinking about assembling a book of very short stories for a long time, given that I keep sketchbooks filled with odd vignettes; a doodle of a giant reindeer looming over a sleeping suburb, a small car in a troubled landscape, someone cleaning a missile in their backyard and so on (the small drawings on the endpapers of Suburbia are intended to reflect this random sketchbook approach). My doodles are often like strange cartoons, concise and with limited narrative; and while all of my stories begin this way, many of them would not endure elaboration into longer forms. My feeling is that they would lose their charm and mysteriousness.

Sketchbooks are great for discontinuity, though this also tends to make them unpublishable – crude, clumsy, incoherent, and unedited. But the fragmentary structure itself, as an idea, is interesting. It’s something I have explored previously in ‘The Red Tree’, a book also descended from free-roaming sketchbook vignettes, dropping conventional linear storytelling in favour of discontinuity, almost as a theme in itself. Images in The Red Tree came from very mixed sources of inspiration. Similarly, all of the stories in ‘Suburbia’ are the products of ‘homeless’ sketchbook doodles and half-articulated ideas – those that I have found especially intriguing, or accidentally poetic in some way. My favourites are usually the ones I can’t fully explain.

Like an exhibition of paintings, an ensemble of different stories can also evoke a single collective concept, something greater than the sum of its parts. I’m not sure that I can articulate that concept, and perhaps it cannot be expressed outside of the book, its particular combination of words and images. But it does have something to do with my experience of growing up in quiet suburban landscape.

Perth is the most isolated capital city in the world, and our family home was built at a northern periphery, which at the time was in a semi-developed condition; we would take shortcuts through the bush to get to the supermarket, to school and to enormous sandy beaches beyond wild dunes. (Tim Winton, who grew up in neighbouring suburb, often writes about the same coastal landscape.)

Northern suburbia did feel at that time like the edge of the world, relentlessly ordinary, yet also liberating in being so quiet and uncluttered, and not without a strange beauty. A lot of my paintings as an adolescent are large canvases depicting silent suburban landscapes: empty footpaths, shady parks, rows of blank-faced houses, deeply shadowed windows and wide roads, things I saw everyday. The other half of my artistic interest was preoccupied with something almost contradictory: science fiction and fantasy, strange worlds far beyond everyday observation. This remains true of my creative work as an adult: half of my attention is fixed upon everyday suburban landscapes, which I often photograph and paint, while much of my time is spent drawing imaginary characters and fictional worlds. I find both equally fascinating.

'Endgame' 1996, house paint and oil on board, 110 x 120cm. One of a series of 'crow' landscape paintings referencing the northern suburbs of Perth, WA.

I’m often looking for ways to bridging those two interests, an ambition made obvious in Tales from Outer Suburbia. Many of the book’s images refer directly to places I have visited or lived within, and are imbued with the same kind of atmosphere that exists in my ‘real world’ paintings. At the same time, the stories and illustrations feel very removed from anything real. I think each story is galvanised by that difference or tension, trying to bring reality and fantasy together, in a way that feels honest and correct – at least as a faithful ‘parallel world’.

There is a similar dialectic between my childhood memories (and often child-like characters), and my more mature concerns as an adult (eg. politics, relationships, philosophy). So each story is a fusion of all those elements – reality, fantasy, childish play and adult reflection. I think many artists would identify with this, recognising that the desire to paint, draw and make up stories begins in childhood, and is inherently playful.

These are some of my thoughts on the book. Beyond that, I’m wary of trying to explain my stories too much, as this might only interfere with another reader’s imagination, which will always be different from my own. I don’t think much about ‘meaning’ when I start writing or drawing, and feel no great need to define it afterwards. I’m simply motivated by one or two images or concepts that I find very interesting, which make sense, but are also unfinished and require interpretation. With that in mind, the following is an account of some sources of inspiration, in response to that common query, ‘where do your ideas come from?’

A description of media used also accompanies each title. I chose to use different styles and media, because I wanted to treat each story individually, as a separate little universe (which is how they were more or less conceived). I used materials and techniques that I felt suited the atmosphere of each tale, as well as quoting such things as Japanese woodcut prints, Italian frescoes and common newsprint.

The Water Buffalo

(acrylic and oils on paper)

This character began as a sketch of a bull, standing upright, pointing into the distance; then I drew him addressing a small girl holding a box. Later the bull transformed into a water buffalo, perhaps because this is an animal I find especially unreadable, tranquil and lethargic perhaps, or brooding and dangerous, and generally unfamiliar to me.

At the time I was often walking past a vacant lot full of wild grass and weeds, existing like a silent pause between very neat suburban houses. I’ve long been intrigued by fenced vacant lots, as if something has been suddenly removed, and is now totally forgotten. This particular square of land seemed to ‘belong’ to the water buffalo in my head, a place where he might live and provide a useful community service. The story (and final illustration) emerged from these two ideas.

Eric

(graphite and coloured pencil on paper)

‘Eric’ was originally a name written underneath a pointy-headed character carrying a tiny suitcase, drawn in a sketchbook while on holiday. I often draw characters and give them ordinary names like ‘Bob’, ‘Dave’ or ‘Alan’ (which I find very entertaining for some reason), but this ‘Eric’ seemed especially amusing and believable. I wondered what his story might be.

Much later, my partner and I had a Finnish friend come to stay with us in Perth. He was a great guy, but very reticent (not uncommon for Finnish men) and often it was unclear as to whether he was happy or not about our planned outings. He was very polite and agreeable, but seldom expressed opinions. So the story is largely about the kind of anxiety that can arise when hosting a guest, as well as more general issues of cultural miscommunication.

A second source of inspiration was our budgerigar (a small native Australian parakeet) named Eddie: a small chattering person in a powder-blue vest who roamed throughout the house finding tiny objects to play with, and constantly announcing his presence with bright chirps, squeaks and chatter. Once I combined these two experiences, our Finnish house-guest and Eddie the budgie, the basic idea for a story emerged. The ‘pantry garden’ may have been inspired by my brother’s childhood hobby at one time of growing ‘crystal gardens’ in tiny aquariums.

Broken Toys

(gesso, acrylic and oils on paper)

The diver in this story makes an implicit reference to one aspect of Western Australian history that most readers are unlikely to know about (nor need to in order to enjoy the story). In the nineteenth century, a flourishing pearling industry grew around the remote town of Broome in the state’s northwest, which attracted thousands of workers of many different nationalities, mostly Japanese. The work was extremely dangerous; divers braved drowning, cyclonic storms and the bends (decompression sickness), an often fatal illness not fully understood at the time. Most of the 900 graves in the Japanese Cemetery in Broome belong to pearl divers, many of those victims of the bends.

The story ‘Broken Toys’ developed from a drawing of an old-fashioned deep-sea diver approaching a suburban corner deli (one near my home), which naturally raised for me the question of why he was there, and where he came from. A second idea came from the fact that as children, my brother and I often lost toys over the back fence into a neighbour’s yard, although I’m happy to say that they never came back chopped in half as they do in the story.

Distant Rain

(pencil, acrylic, oil & paper collage, using other people’s handwriting)

This idea began when I was thinking about Jewish stories of the Golem, an artificial being made of clay that could be animated by spoken or written words (‘golem’ in Hebrew means ‘shapeless mass’, also ‘unformed’ or ‘imperfect’). This lead to the idea of a being made out of words – particularly those written on scraps of paper, thrown away or lost. Eventually the story evolved into something a little like the narrative of a wildlife-documentary, and the ‘paper being’ simply became a large ball with some kind of vague consciousness.

A second reference point: my Dad used to work as an architect, in a pre-digital time when everything was hand drawn on big sheets of translucent paper, taped down with small bits of masking tape. He had a habit of putting all the old bits of masking tape together as a single mass, which over time became a little larger than a softball, always sitting next to his drawing table (he made a few of them over the years). When Dad left one office, his co-workers had secretly painted one of these masking-tape balls gold, mounted it on a block of wood, and presented it to him as a trophy. This left a strong impression on me as a child, seeing this strange object on the living-room shelf that was somehow meaningful, yet made of ‘waste’.

Undertow

(oil on wood)

One source for this story was a visit to Shark Bay, a northern WA town known for friendly wild dolphins (in Monkey Mia), but also a population of dugongs, a rare sea mammal similar to a manatee. Another was a childhood memory of a boy who lived near our home and seemed to spend almost all of his time hitting a tennis ball against the wall of a brick shed in our local park. It was a bleak and melancholy sight that remained unchanged for years, as if the boy was trapped in a kind of suburban purgatory.

Grandpa’s Story

(ink, watercolour and ball-point pen)

A friend’s wedding prompted me to think about strangeness of western-style weddings in general – particularly the more old-fashioned idea of tying objects (usually boots and tin cans) to the back of a married couple’s ‘getaway car’, perhaps an ancient tradition to do with warding off bad spirits.

Another experience that informs this story involves my family’s participation in a scavenger hunt when I was very young. This involved driving around Perth in our old Datsun and answering a list of questions (eg. what is on the large billboard next to the bridge?). I have no idea of the purpose of this adventure, probably a prize for the first to return. My parents and brother don’t seem to remember anything about it. All I can recall myself is that we got lost and Mum and Dad had an almighty argument over vague instructions or poor map-reading, one of the more common curses of family car trips!

In my sketchbook I started drawing little pictures of a newlywed couple in an old car encountering all sorts of ‘testing’ perils, many of which developed into the final illustrations that make up the silent middle-section of the narrative. I hope that couples in a close relationship might be able to identify with some of these scenes. To me they have something of a mythological feeling, referencing ancient stories to do with a rite of passage in a desert, or being cast out into the wilderness in order to ‘graduate’ to a new level of self-understanding. In this case, it happens beyond the edge of outer suburbia, past the very last railway line, a treacherous place without logic or comfort.

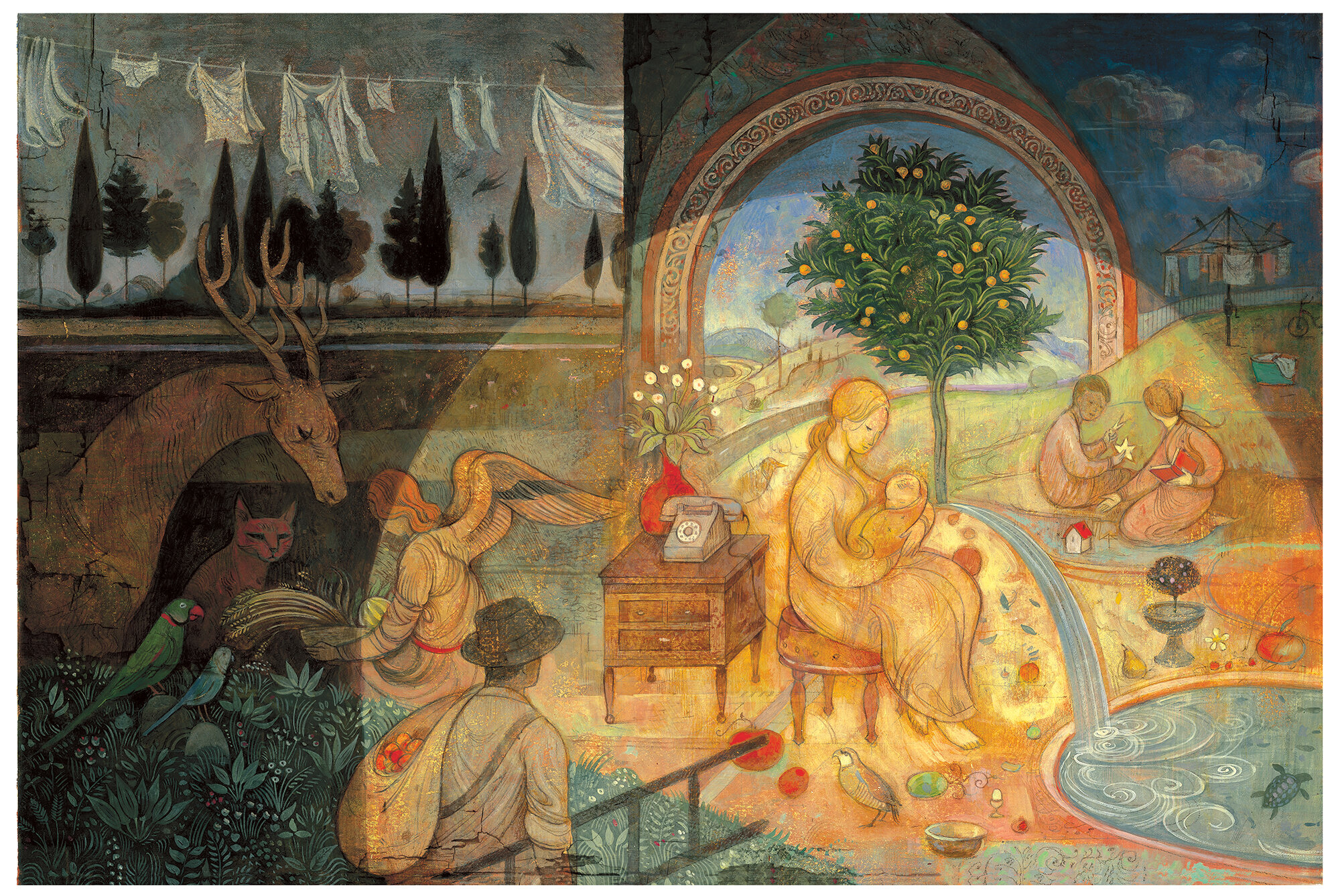

No Other Country

(acrylic, oils, coloured pencil, digital)

Growing up I often had Italian friends and neighbours, without knowing a great deal about their cultural background. It has only been in recent years that I’ve visited Italy and returned with a greater sense of that country’s long, deep and complex history, so physically evident in the urban and rural landscape. I have since thought a lot about the difference between Australian and European towns, and considered how waves of Mediterranean immigrants must have felt arriving in Perth during the 1950s - not the most cultured or cosmopolitan city in the world at that time – and then often treated as second-class citizens. This is something I began researching for another book, The Arrival.

I read one story of an immigrant who referred to ‘the curse of two countries’. He spoke of the tendency to idealise one’s homeland in the face of problems and disappointments experienced in a new place; ‘it’s never as good as home.’ Yet when he revisited the Italian town of his youth as an older man, he realised that it was not actually the nostalgic place constructed in memory (one that overlooked certain flaws and annoyances). Moreover, it was also greatly transformed due to social and technological change, such that the ‘Old Country’ now existed only in his imagination. My small story takes some inspiration from this condition, the ‘curse of two countries’, and also its simultaneous ‘blessing’: the opportunity for a richly imagined, internal landscape, the immigrant’s ‘inner courtyard’.

There are two other sources for this story: the fact that our plastic Christmas tree really did once melt in the roof-space of our family home (due to a fierce Perth summer); and a visit to the Santa Maria Novella in Florence, which has a very peaceful inner courtyard, not unlike the one featured in my illustration.

The Nameless Holiday

(scraperboard / scratchboard)

This came from thinking about a possible counterpoint to Christmas, and any tradition that involves receiving gifts at a certain time of year (especially those delivered by fantastical people or animals). I wondered if there would be any value in a celebration that involved an equivalent sacrifice; instead of listing what you want, you have to think about what you are prepared to lose. I also like the idea of a weird celebration with no fixed calendar date, that could happen anytime in August or October, but for some unknown reason, never the month in between.

Christmas in Australia is really a surreal experience; a transplanted European tradition that specifies reindeer, snow, roasts, holly, puddings, sleds and other things that are foreign to the antipodes, where Christmas day is often swelteringly hot and the only ‘snow’ children would ever see came from a spray-can or a recently defrosted freezer.

The Amnesia Machine

(graphite pencil, digital)

This story was triggered by an article in a newspaper, featuring a picture of an enormous prefabricated section of an oil or gas refinery being transported through the street of a rural town, with a crowd of locals looking on. I had this image cut out and taped into an old sketchbook for years, and have drawn different versions of it, but have since lost the source reference. The original caption had some remark about the object looking like an alien spaceship, but I found the idea that it could be an object built by humans to be a far more sinister and intriguing concept. Especially if its purpose was secret, while it’s presence was openly visible to the public.

The phrase ‘amnesia machine’ or ‘amnesia factory’ has long been in my mind as a way of describing political campaigns and electioneering, skilled as they are in the ancient arts of distraction, omission and obfuscation; as well as media coverage of divisive political issues (such as refugees, war and race relations), the rise of neo-conservatism, and some alarming issues of media ownership, bias and conflicts of interest. It’s not so much an issue of conspiracies, but rather a failure of critical vigilance, and public apathy. I was especially mindful of a book by Don Watson, ‘Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language’ (about a recent proliferation of vacuous ‘corporate-speak’ in Australia); the paintings of Jeffrey Smart, particularly one entitled ‘Factory Staff, Erehwyna’, which also features an ominous background machine operated by a team of contented, oblivious suburbanites.

Stick Figures

(acrylic and oils on paper)

This ‘story’ has a very interesting source of inspiration: a large outdoor installation by the side of a highway in Lapland called ‘The Silent People’. It is a crowd of several hundred scarecrow-like figures in a field, each made of a cross of wood, dressed in second-hand clothing, with a clod of grassy earth for a head stuck on top. The effect is both amusing and eerie, like whimsical ancestral beings or puppets.

All of the paintings in this story represent the immediate environment of my childhood and adolescence, in the sprawling northern suburbs of Perth; people who live there will recognise this immediately. It’s a vast, quiet landscape that I’ve been attracted to as a subject for painting over many years. In my early twenties I painted several works featuring local streets, populated only by a few crows. Sometimes the crows were fighting or gathering on power-lines, but mostly they were just standing around, as if waiting for something to happen (long, wailing crow calls in the sunburnt afternoon air feature strongly in the soundtrack of my childhood).

‘Stick figures’ is a combination of these two ideas, crows and Lappish ‘silent people’, but moreover relates to my feelings about the rapid, large-scale clearing of bush-land to make way for fresh roads, homes and shopping malls. Too often things seem to be built without a proper acknowledgement or empathy with the natural landscape – it is simply swept aside as if it never existed, replaced by an amnesiac culture. One of the few remnants of the original forests are big tuart trees in parks, ancient sentinels that tend to drop long, angular sticks from time to time. If you stand them up, they sometimes look like human figures.

Alert but Not Alarmed

(acrylic, gouache and coloured pencil on paper)

This piece is something of a positive flipside to ‘The Amnesia Machine’, suggesting that ordinary people can have a healthy scepticism of authority. The title comes from an Australian Federal Government campaign warning the public to ‘Be Alert But Not Alarmed’ in respect of an unprecedented terrorist threat to Australia resulting from our participation in the war against Iraq. A lot of people were quite critical of this, feeling that it was intended to inspire public paranoia, as much as abate it, and perhaps legitimate some questionable government decisions and claims.

However, the real idea for this story came from an anecdote told to me by a taxi-driver one day on my way to an airport. He described an incident in Lebanon where a dud missile had somehow ended up in the middle of a suburban street, and some local people seized the opportunity to take it home, disassemble it and sell it off as scrap metal. It provoked a secondary scenario in my mind, of children finding an unexploded missile, and converting it into a ‘space rocket’ cubby-house. The final story and image evolved from that germinal idea.

Wake

(graphite pencil on paper)

Like ‘The Water Buffalo’, this story was preceded by a finished illustration, one that developed from a rejected concept doodle for a rock album by a New York band. I have a large stash of rejected sketches, from a time when I used to take on a lot of commissions, but this was one that I particularly lamented as a missed opportunity because the image was very evocative.

Whenever I look at pet dogs of all shapes and sizes, I can’t help thinking about ancestral wolves, and what distant memory might still be lodged in the domesticated canine brain. Dogs are naturally pack animals, yet more often than not find themselves alone, fenced into the tiny territory of a suburban backyard. I can’t help feeling that by taking dogs (and other pets) away from nature via centuries of domestication, humans now have a special duty of care, and any wilful neglect of this is unforgivable.

Make Your Own Pet

(acrylics, oils, pencil, photocopied text and paper collage)

This is the oldest illustration in the book, originally produced for a collection published to raise funds for the RSPCA, entitled Animal Scraps: a bumper book of animal stories (Omnibus Books, 2003). Different writers and illustrators were asked to each contribute an anecdote or observation of their favourite animal or pet. I had originally started to write something about my cat Punj, a small, part Siamese waif who was short-sighted, partly deaf and generally neurotic - and very companionable - who sat next to me for the better part of twelve years. I had adopted him through an ad in a local paper, from a family who did not want him anymore. The more I thought about Punji, the more I saw him as a triumph of ‘recycling’, and realised this was an ideal RSPCA theme, where abandoned animals are often given new homes.

At the time of this project, my neighbourhood was having a ‘bulk rubbish collection’ week, so there were piles of interesting junk and spring-cleaning detritus lining the footpaths (and I can’t help checking them out for anything useful!). The parallels between people throwing out objects that were once exciting purchases, and the adoption of ‘second-hand’ pets seemed too obvious to ignore.

Our Expedition

(pastel crayon)

Years ago I had drawn a small picture of two boys looking over the edge of a cliff that appeared in the middle of a suburban landscape, something like those ‘edge of the world’ visions from days when mariners thought the earth was flat. So this story began with an ending, and I can’t help but identify the two characters as being myself and my brother (who is about a year older than me). As in the story, we often used to argue about trivial conjectures. I’ve also owned street directories where essential pages have fallen out, suggesting the idea of a ‘cut off’ map.

As kids my brother and I once walked home across two or three suburbs, having no other means of transport due to a bus strike. It seemed to take forever, and really made me think about the scale of suburbia, not just its size, but its relentless repetition of ideas – housing styles, parks, shopping squares, and identical roads that seemed to have no end. This is the story that best captures for me the feeling of a suburban childhood, and the psychological boundaries that can be created by spending a long time in any one place (I did not really travel outside of Perth until I was a teenager). When everything you need is locally available, and experience is routine, it can be hard to imagine other places or ways of living – the whole world becomes small and shrink-wrapped.

Night of the Turtle Rescue

(graphite pencil on paper)

This ‘story-image’ is also partly inspired by the work of two friends, Gerald and Guundie Kuchling, who have devoted much time and effort to the rescuing critically endangered turtles. The image, however, developed separately as a sketch of a small car being chased by a huge, ominous truck through an industrial area (outer outer suburbia) in the middle of the night. It seemed like a scene from a nightmare, or an attempted escape from Hell; the addition of little turtles in a back seat or tray also suggested a rescue effort. How and why? And what’s been happening with the turtles? These questions seem most interesting when left unanswered.

Many of us are mindful of the dilemma that accompanies some social, political or environmental activism: a great deal of work and passion can be invested into projects that may have uncertain rewards or effects. And even the cause itself may be called into question: it is easy to lose heart in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, which is true of so many life situations.

The real danger of suburban life is complacency, and it’s easy to forget that our lifestyle of consumption and expansion is linked directly to vast industries, and the toll they extract on the habitats of other animals. Our lives are quite abstracted from the natural world that we depend upon everyday, both geographically and psychologically, and this is something that I feel runs through many other stories in the collection, a sense of brokenness or disconnection. The question that follows is how we might recognise and respond to this.

Our Tuesday Afternoon Reading Group

(acrylic and oils on paper)

Reading can bring us together as a shared passion, but also reveal how highly individual we are. I could think of no better way to represent this than painting an oddball reading group comprised of very different creatures, who likely have very different perspectives, tastes and opinions. Yet they are bound together by the kind of universal ideas and feelings that books can offer; here taking advantage of the last of the afternoon light in outer suburbia.