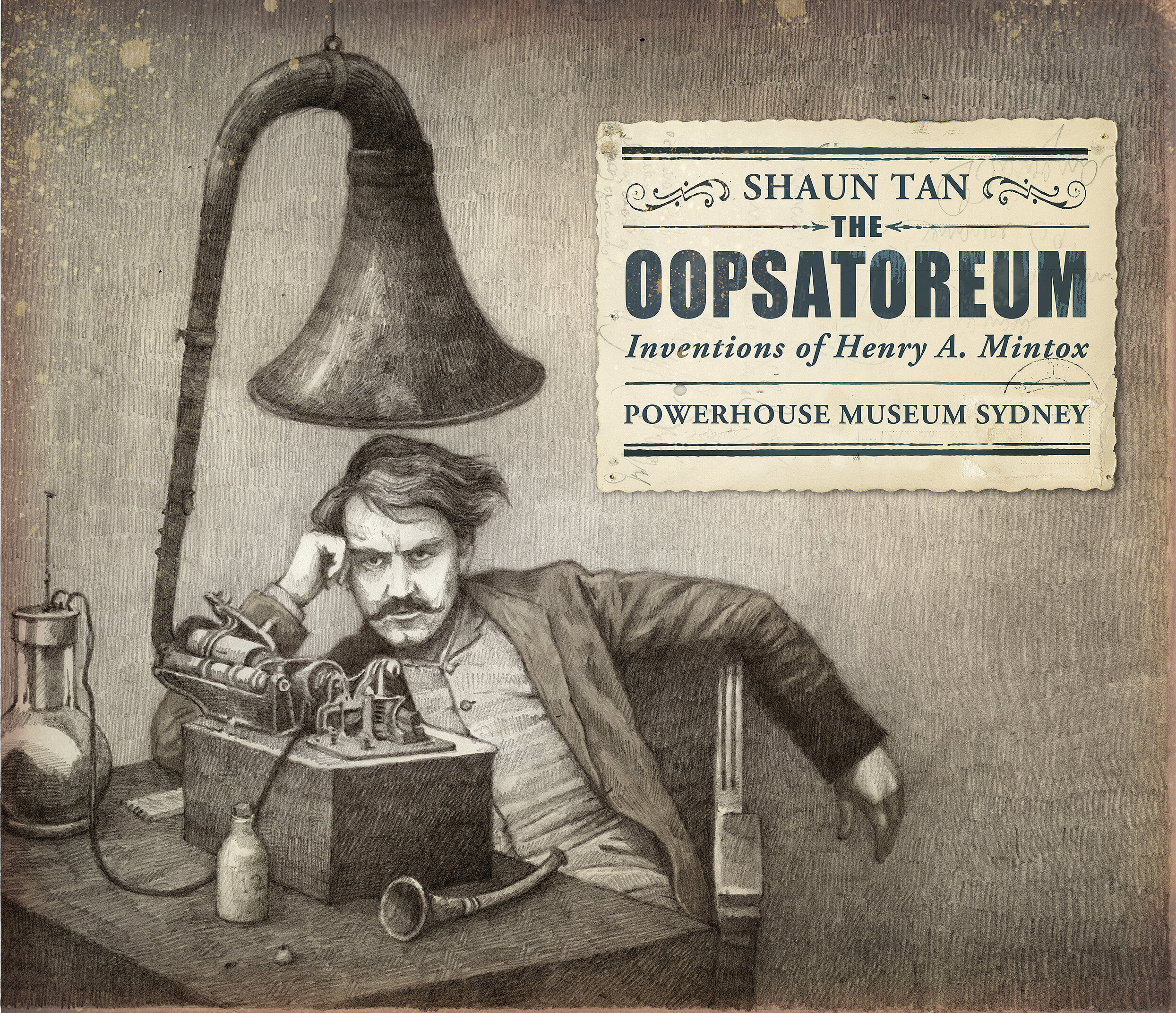

THE OOPSATOREUM

Maude, pencil, digital, 40 x 40cm

Cover illustration for the accompanying book for the exhibition, a portrait of Henry Mintox demonstrating his 'Inspiration Recorder' in 1922 (based on a photo of Thomas Edison testing an early phonograph).

Following on from the successful exhibition of curiosities, The Odditoreum (2010), in which I wrote imaginary labels for real curiosities from the Sydney Powerhouse Museum basement, Program's Producer Helen Whitty approached me with a concept for another show involving fictional histories of real (but often quite strange) objects from their archives. While the Odditoreum wandered randomly from medieval canonballs to genetically engineered moths, Helen's idea for the Oopsatoreum involved more of an overarching narrative, with some emphasis on mechanical objects and accidents. I responded with the character of an imaginary inventor, Henry A. Mintox (pictured above): spectacularly unsuccessful and therefore largely unknown, at least until this museum 'retrospective'. Many of the actual objects, from a hearing-aids to a mechanical dog, are recast as failed innovations. In some cases being too far ahead of their time, such as an early attempt to introduce mobile text-messaging using analog technology. Beneath the silliness of the project there is actually an important observation: all invention begins as a daring act of imagination, and beings with a play of outlandish ideas. For every success that filters into daily use, there are countless failures that are as important a testament to creative spirit. The book was published in 2012, and the exhibition opened at the Sydney Powerhouse Museum in 2013. Below are some examples of my ‘fake labels’ based on random museum objects.

Fat Suit

In 1931, Henry Mintox received his first – and last – invitation to present a keynote at the British Inventors Club annual conference in London. Believing obesity to be a sign of wealth and success, especially during the Great Depression, Henry fabricated a special ‘enhanced undergarment’ to be worn beneath a new suit for the duration of his visit, so as to impress his audience. Unfortunately the family tailor fitted Henry’s shirt, waistcoat and jacket to his usual body measurements, a mistake realised only upon unpacking in England. Persisting with the original plan, Mintox’s suit seams burst during an especially animated part of his lecture about steam pistons. The deceptive undergarment was suddenly exposed in plain view to much ridicule and hostile booing – especially from those spectators who were genuinely obese industrialists. Ironically, just as Henry left London in humiliation, tailors of the East End began manufacturing similar undergarments in earnest. As the Depression deepened throughout the 1930’s, these ‘fat suits’ were frequently sold to undernourished entrepreneurs seeking to impress potential investors with their ‘affluent’ girth.

Tiger Shark Shoes

Henry Mintox’s favourite pair shoes were custom-made according to his own design, made from the skin of a tiger shark caught during a fishing trip in the South Pacific. While Mintox loved hunting trophies he also detested most forms of taxidermy, and considered wall-mounted trophies especially disrespectful of any creature that naturally craved motion and adventure, even in death. By associating an animal’s skin with some form of locomotion, he believed he could both honour and brag about a kill in good conscience. We can see this philosophy practiced religiously through other custom-made travel accessories (since auctioned off to fund conservation efforts): a fedora hat fashioned from a whole duck, a seal-head bicycle seat, matching koala suitcases and a jaguar hood ornament, made from an actual jaguar.

1926 model Austin Tourer

This is the car Mintox planned to drive from Melbourne to Davenport, a daring feat touted as ‘the first ferry-less automobile crossing of Bass Strait’. He proposed that a series of long wooden planks were to be dropped into the sea from one boat, and collected again by another following, such that a temporary floating ramp formed between them that might be negotiated by a suitably skilled motorist. Unfortunately, the laws of physics conspired against the plan during an initial test-trial on a local duck pond, as did the laws of his insurance provider. The project was shelved ‘until further notice’. Fortunately, this means that a very well preserved 1926 Austin Tourer is now available to museum visitors, rather than languishing at the bottom of the sea.

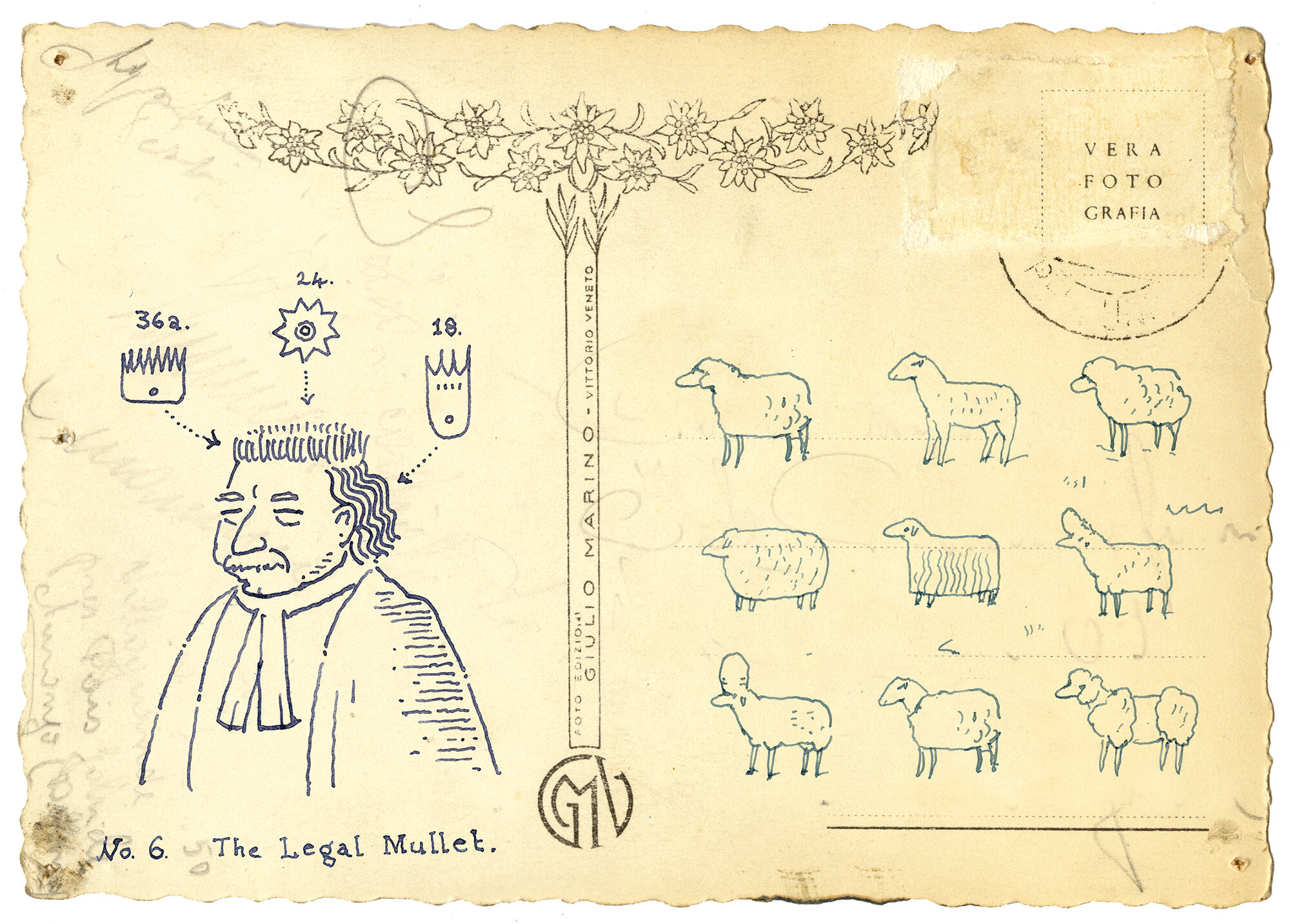

Brooch from the Future

Although Mintox rarely kept any journals (preferring cryptic doodles on postcards), much of what we know of his work was dutifully recorded in the diaries of his wife, Maude. She makes particular mention of Henry’s claim to own a piece of jewelry ‘from the future’, and object supposedly acquired with the aid of an invention he refused to speak about for fear of ‘disrupting the space-time continuum, leading to inevitable self annihilation’. Maude speculated that this could be a strange metaphor for marital infidelity, and that the brooch – discovered while vacuuming behind a couch – might well have a less science-fictional origin. It remained a difficult topic of conversation, or rather non-conversation, between Henry and Maude for many decades. Interestingly, an identical brooch was reported to have mysteriously disappeared from a contemporary exhibition in 2008 during an electrical storm, and never seen since – until now. Such evidence of possible time-travel has, unfortunately, missed putting a suspicious mind at ease by about half a century.

Magic Lantern

One of Mintox’s most treasured possessions as a young man, this magic lantern was used to beguile audiences with full-colour image projections in the early 1900s, the centre piece of a traveling show entitled ‘Visions of Tomorrow’. Against common expectation, Henry’s elaborate hand-painted slides depicted scenes of industrialized warfare, at once disturbing and strangely prophetic: machine guns, mustard gas attacks, air-raids, even ‘military rockets’ and ‘uranium powered explosions’, all intended as a cautionary plea for world peace in the coming century. Mintox believed that children, as the future leaders of society, were the world’s best hope for averting such possible horrors and therefore an ideal audience for the show. Parental groups did not agree: the magic lantern tour was cancelled immediately after it’s opening night. It only resumed when, in desperate need of income, Mintox turned to painting dragons, fairies and unicorns, attracting sell-out crowds and rave reviews. The tour was only interrupted in 1914 when Mintox was conscripted for military service in WWI.