THE RED TREE

Dawn, 2000, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

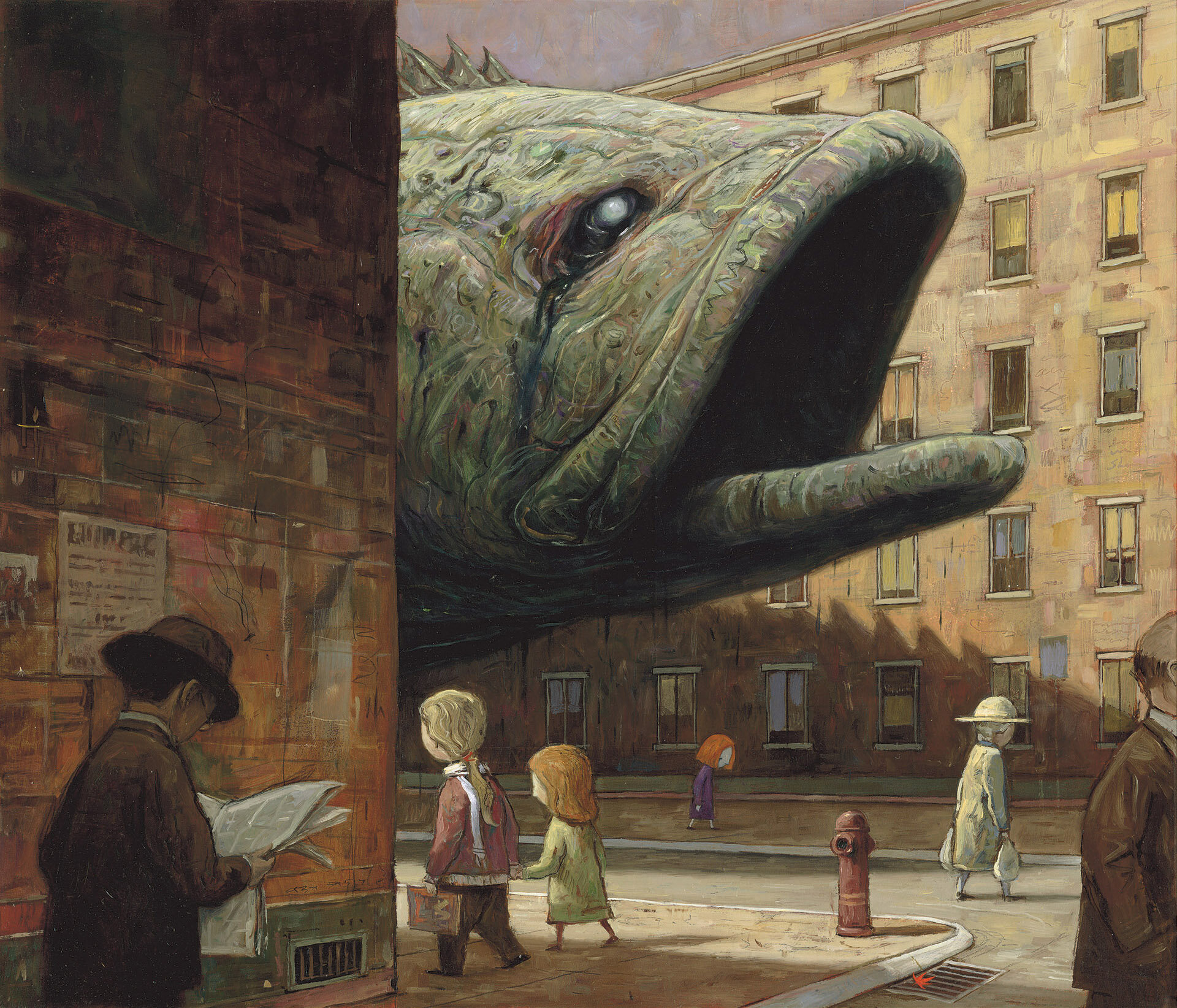

Darkness (detail), 2000, acrylic and oil on paper, 50 x 45cm

Reflection, 2000, acrylic and oil on paper, 70 x 50cm

Fate, 2000, acrylic and oil on paper, approx. 50 x 45cm

Self Portrait, 2000, acrylic and oil on paper, approx. 50 x 45cm

The Red Tree (detail), 2000, acrylic and oil on paper, 40 x 60cm

The Red Tree is a story presented as a series of distinct imaginary worlds, self-contained images which invite readers to draw their own meaning in the absence of any explanatory narrative. As a concept, the book is inspired by the impulse of children and adults alike to describe feelings using metaphor - monsters, storms, sunshine, rainbows and so on. Moving beyond cliché, I wanted to paint images that would further explore the expressive possibilities of this kind of shared imagination, which could be at once strange and familiar. A nameless young girl appears in every picture, a stand-in for ourselves; she passes helplessly through many dark moments, yet ultimately finds something hopeful at the end of her journey.

The Red Tree won the Patricia Wrightson prize in the NSW Premier’s Book Awards, and was awarded the 'le Prix Octogones 2003’ prize by the Centre International d'Etudes en Litterature de Jeunesse, following it’s translation into French. It has been translated into multiple languages, and in the US appears in the volume Lost and Found, published by Scholastic.

*

The Red Tree began an experimental narrative more than anything else: the idea of a book without a story. I've always loved Chris Van Allsburg's classic picture book ‘The Mysteries of Harris Burdick’ (1984) which is a great example of word-picture enigmas, exhibiting partial fragments of unknown stories and allowing the reader to use their imagination. It has no sequential narrative, which is something for which a picture book is ideal – you can open it at any page, go backwards or forwards, and spend as much time as you wish with each image.

I'd also been increasingly aware that illustration is a powerful way of expressing feeling precisely because it lies outside of verbal language, as many emotions can be hard to articulate in words. I thought it would therefore be interesting to produce an illustrated book that is all about feelings, unframed any storyline context, in some sense going ‘directly to the source’.

What resulted after many scribbles was a series of imaginary landscapes connected only by a minimal thread of text and the silent figure of a young girl at the center of each one, with whom the reader is invited to identify. At the beginning she awakes to find blackened leaves falling from her bedroom ceiling, threatening to quietly overwhelm her. She wanders down a street, overshadowed by a huge fish. She imagines herself trapped in a bottle washed up on a forgotten shore, or lost in a strange landscape. She's caught in a tiny boat between towering ships about to collide, then suddenly she's on stage before a mysterious audience, not knowing what to do. Just as all hope seems lost, the girl returns to her bedroom and finds a tiny red seedling growing in the middle of the floor. It immediately grows into a vivid red tree that fills her room with warm light. Each image remains open to various interpretations in the absence of any accompanying description. What minimal 'story' there is seeks to remind us that just as bad feelings are inevitable, they are always tempered by hope.

Originally I was planning to paint pictures about a range of emotions; fear, joy, sadness, love and so on. But the more I worked on this, the more I found the negative emotions - particularly feelings of loneliness and depression - were just much more interesting from both a personal and artistic point of view. Not that I’m an unhappy person – although I do have first-hand experience of depression – it’s just that these ideas seem to be ultimately more thought-provoking on the page.

Readers have occasionally asked me why my imagery is so often 'dark', and I think it’s because of this. I'm more attracted to those things that aren't quite right, like the social and environmental injustice in The Rabbits, or the social apathy of The Lost Thing, or even ideas about self-destruction in The Viewer. I find such things artistically engaging, perhaps because they are unresolved, like a puzzle, or a fear to be overcome. At the same time, I do enjoy work that is celebratory - which The Red Tree ultimately is - but any apparent meaning is always laced with uncertainty. The red tree may bloom, but it will also die, so nothing is absolute or definite; there needs to be an accurate reflection of real life, as something continuously in search of resolution.

The Red Tree has been translated into several languages which indicates something of its cross-cultural appeal. A different kind of ‘translation’ altogether has been the adaptation of this book as a children’s theatre production several times in Australia and abroad, been the subject of a concert by the Australian Chamber orchestra and the inspiration for many muscians: classical, folk, jazz, rock, experimental. Moreover, The Red Tree has been used extensively by medical and mental health professionals as a support for discussion about emotional health, from palliative care to psychiatry. In many cases, not just for patients, but for their family and friends to better understand a patient’s experiences. The book has also figured prominently in the Winter Solstice event, supporting survivors of suicide.

The ideas of the original book are very broad and I think point more to a method of expression rather than any very specific content, so it not only endures variable interpretations, it needs them. This seems appropriate, as everyone’s experience of ‘suffering’ or ‘hope’ is unique and personal. It’s a different book to different people.