THE LOST THING (BOOK)

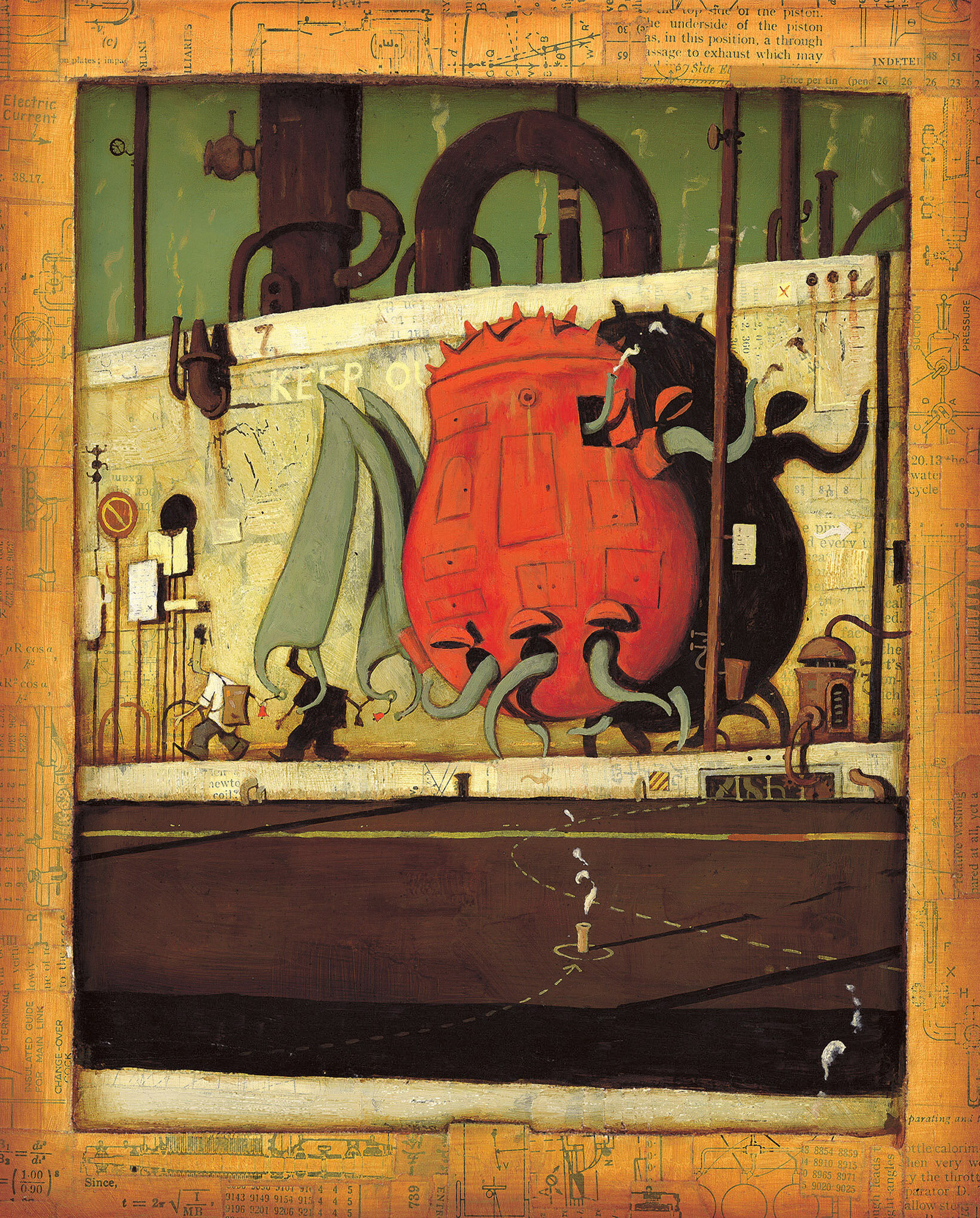

Beach (detail) 1999, acrylic oil and collage on paper, 70 x 50cm

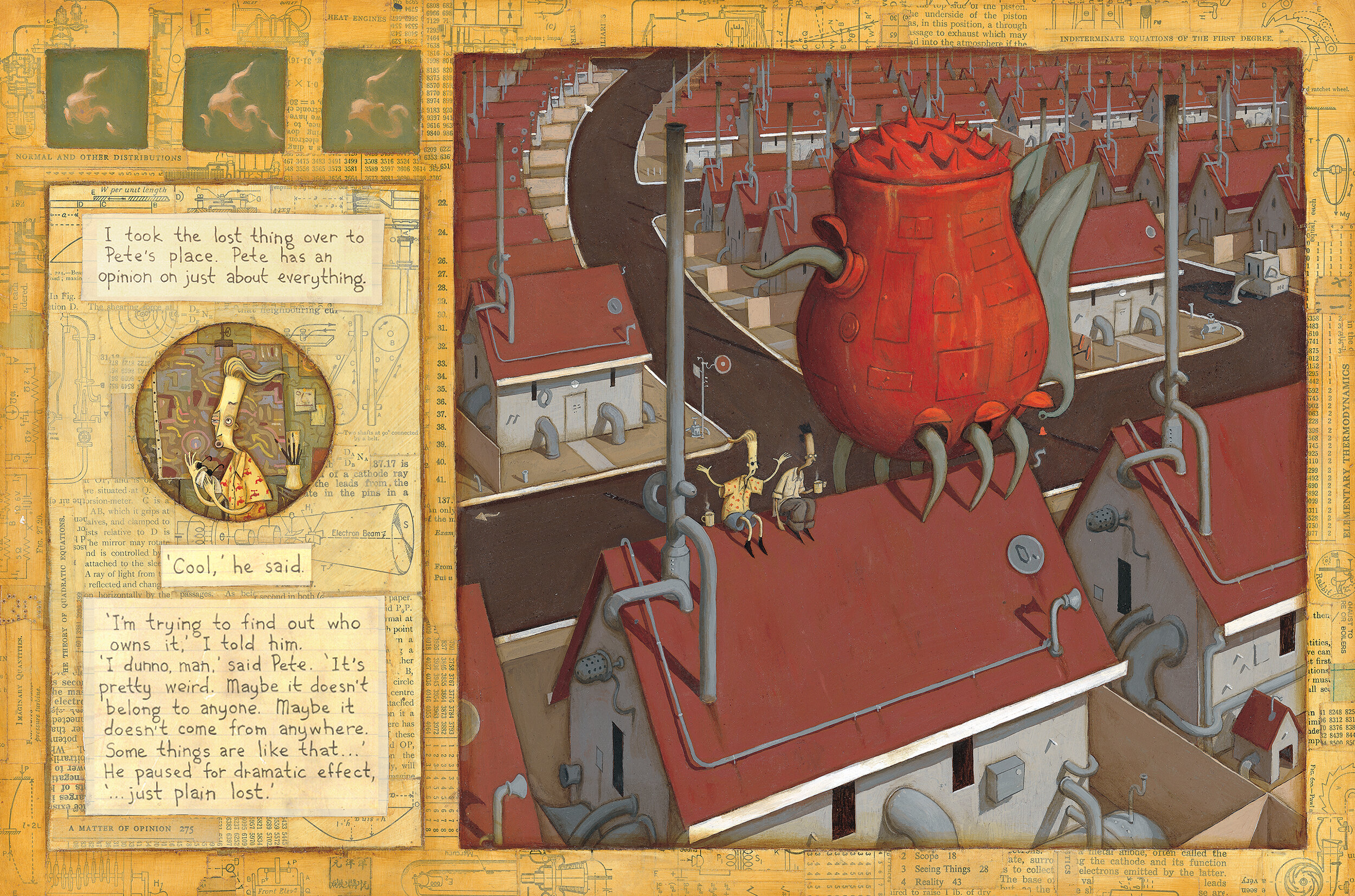

Hello! (detail) 1999, acrylic oil and collage on paper, 50 x 60cm

Walking home (detail), 1999, acrylic oil and collage on paper, 50 x 60cm

The Federal Department of Odds and Ends (detail), 1999, acrylic oil and collage on paper, 70 x 50cm

The Lost Thing is a humorous story about a boy who discovers a bizarre-looking creature while out collecting bottle-tops at the beach. Having guessed that it is lost, he tries to find out who owns it or where it belongs, but the problem is met with indifference by everyone else, who barely notice its existence. Strangers, friends, parents are all unwilling to entertain this uninvited interruption to day-to-day life. In spite of his own reservations, the boy feels sorry for this hapless creature, and attempts to find out where it belongs.

The Lost Thing received an Honourable Mention at the Bologna International Book Fair, Italy and an honourable mention at the CBCA Awards. In 2020, The Lost Thing won the Phoenix Award in the US, given twenty years later to a book that did not win a major award at the time of publication. Original illustrations from the book have been exhibited at the Itabashi Art Museum in Tokyo and eslewhere in Japan, Germany, Sweden and the UK.

In 2010 I wrote, co-directed and designed a 15 minute animated adaptation of The Lost Thing which went on to win an Oscar at the 83rd Academy Awards. You can read more about the film here.

In 2012, an exhibition produced by ACMI, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Shaun Tan’s The Lost Thing: from Book to Film, showcased illustrations, drawings, interviews and props created for the film and toured throughout Australia over following years.

*

What started out as an amusing, nonsensical story about a freak soon developed into a fable concerning serious social issues, with a rather ambiguous ending. I became quite interested in the idea of a creature or person who really did not come from anywhere, or have an existing relationship to anything, and was ‘just plain lost’ as one character puts it. I wanted to tell the story from the point of view of a teenage boy, that would represent how I might personally respond to this situation.

I wrote the story over a couple of weeks on my kitchen table - the original draft was much longer and more detailed, and was set in an ordinary suburb much like the one I grew up in. Later that changed as I developed the idea that the it was a kind of ‘retro-future’ suburb where there were almost no living things left, aside from people, and that everything was very dull and suffocating, but nobody cared very much about this.

The text is written as a matter-of-fact anecdote, told by the boy and addressed to the reader, presented as a kind of “what I did over summer” story (hence the use of hand-written text on strips of note paper). Significantly, the creature in question is never physically described, and there is very little said about the environment in which the story unfolds; this is where the illustrations take over. Read by itself the text would sound as though it is about a lost dog in a quite familiar suburb or city, but the pictures reveal a freakish tentacled animal in a surreal a treeless world of green skies, excessive plumbing, concrete and machinery.

The relationship between words and pictures is one of understatement; much of the humour in the story develops from this as the images defy expectation, and all weird absurdities are greeted with a kind of casual disinterest from the narrator. Such a tone is consistent with the themes of the book, which deals with questions of apathy, particularly the suppression of imagination and playful distraction by pragmatism and bureaucracy, conditions that affect both a society and its individuals.

Visually, the book is quite dense, like the world it depicts, having a sense of congestion and compression. There are no empty spaces on the pages, with all images framed by a collage of text and diagrams cut from old physics and maths textbooks. These were used by my Dad when he was an engineering student, and largely inspired much of the book’s aesthetic; they add some sense of the dry and industrial world presented in the paintings, a sort of meaningless functionality - pointless and amusing also. There is an accidental ‘poetry’ that often occurs using collage, where a chapter heading in an engineering manual might pass as an unintentional comment on life. The bottle-top collection, made from many beer bottle-tops (supplied by my house-mate), seems to perfectly sum up the universe in an abstract way - just right for an endpaper design.

I also liked the idea that, in keeping with the first-person narrative, this book is somehow a product of that world. Stamps and signs marking the cover and title pages, eg. “The Federal Department of Information”, are consistent with the society the narrator comes from, along with other incidental details throughout the book which collectively build a sense of the place in the absence of any overt description by our story-teller.

The Lost Thing itself I always knew would be red and big, so very noticeable, which makes us wonder why nobody really notices it (this is the key question of the story, for which there is no single answer). Its design was based on a pebble crab, a small round crustacean with claws that hinge vertically, and I combined this with the look of an old-fashioned pot-bellied stove, with a big lid on top instead of a mouth. I did not want the creature to have any anthropomorphic features, especially no face, so it’s eyes are reduced to small dots which emerge from a hole. The main thing was that it looked strange and unrecognisable - which is not always easy.

The creature exists in contrast to the world it inhabits, being whimsical, purposeless, out-of-scale and apparently meaningless - all things that the bureaucracy cannot comprehend, and so it is not worthy of any attention. Being a curiosity is only effective if the populace is curious, and they aren’t, being always “too busy” doing more important things.

There is perhaps some suggestion that the creature is an accidental by-product of the industrial landscape, a sort of unconscious mutation, appearing on the beach as if ‘washed up’. Towards the end of the book we notice that while the lost thing may be unique, it is not alone - evidently weird creatures regularly appear in the city, but their presence can be measured only by the extent to which they are noticed (ie. generally not at all). What these things are exactly should be a broad and open question for the reader, given that they symbolise some fairly open-ended notion of ‘things that don’t belong’.